WIRELESS OPERATOR / AIR GUNNERS Part: II

(Last updated: 30.04.14 - Vic Reynolds)

Here's the second list of WWII 206 Squadron WOp/AG's, click their photograph for their story...

Vic Reynolds by Vic Reynolds (Feb 2009)

Jim Steel by David Cotterill (2007)

Eric Walker by Trudy Hindmarsh (Oct 2009)

Vic James Reynolds

Rank: Flight Lieutenant

Number: 755865

Joined 206: ??/09/1940

Flew with Ken: 0 times

Born: 07/06/1920

Died: 09/01/2010

In 2008 I was chatting to an Uncle of mine who lived round the corner, I had mentioned my RAF interest and he asked if I'd met the RAF Veteran on my street. I had no idea that a WWII RAF Veteran lived on the same street and duly obtained the chaps phone number.

Days later I made the call and to my great surprise it turned out that a Wireless Operator / Air Gunner called Vic Reynolds resided just 6 doors up, and not only that but Vic had started life in the RAF with 206 Squadron!

Vic Reynolds: Nov 2008

Vic married Dorothy Hilda Juggins during the war in December 1944 and they had 6 children:

'A-Flight'

-

John in 1945,

-

Margaret in 1947

-

Philip in 1949

'B-Flight'

-

Bernadette in 1959

-

Barbara in 1961

-

Christopher in 1963

I've had many interesting conversations with Vic throughout 2008 and 2009 and I've documented the WWII parts of his story.

Rank

-

WWII - Flight Sergeant

-

18.3.1960 - Pilot Officer

-

18.3.1962 - Flying Officer

-

18.3.1972 - Flight Lieutenant

Vic's Uniform and Flying Jacket

Vic's Medals

From Left to Right...

-

1939-1945 Star

-

Aircrew Europe Star with Atlantic Clasp

-

War Medal

-

Defence Medal

-

Air Efficiency Award

-

Cadet Forces Medal (QEII)

Vic Reynold's Story

1938

At this time Vic already had an interest and hobby in Radio equipment and it was in 1938 that he put his name down on the RAF Voluntary Reserve list.

1939

Vic was working on the Potbanks Monday to Friday as well as Saturday mornings, around April of that year the weekend Air Force (RAFVR) started up at Trentham in Stoke-on-Trent and he joined up.

1940

Vic first started Wireless Operator training in 1940, half of his time was at RAF Church Fenton whilst the other half was spent at RAF Linton-on-Ouse. He celebrated his 20th birthday on Friday the 7th June whilst he was training there. After time at Harwell he completed his radio course at Cranwell finishing top of the class in Morse. Finishing so high in the class meant the top 2 bypassed the Operational Training Unit and were advised they would both be joining 206 Squadron. This was now September and on their trip to the Squadron they stayed overnight a Peterborough arriving at Kings Lynn on a Sunday morning. They met up with the Squadron that were based at RAF Bircham Newton in Norfolk.

206 Squadron were in the process of converting from Anson's to Hudson's and once they settled Vic became part of a fixed Hudson crew very quickly and they stayed together throughout the majority of his time with the Squadron. The crew was made up of all sergeants.

1941

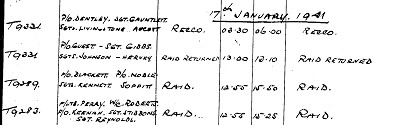

When Vic first arrived with the Squadron he had noted that there were enough Lockheed Hudson's to cover 22 letters of the alphabet in terms of serial numbers, by May 1941 there were just a few left. There are many logs in the National Archives that record Vic's activities with 206 Squadron. One such record I found was a Raid on the 17th Jan with F/Lt Perry, W/C Roberts, Sgt Stibbons, P/O Keenan.

Operational Log 17th Jan 1941

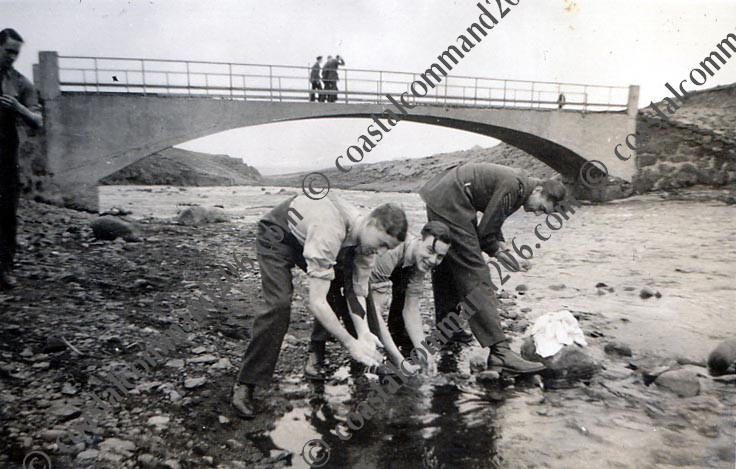

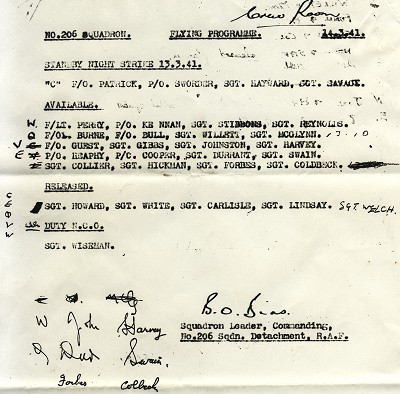

Vic has a Flying Programme that's dated 14th March 1941 that details the different crews that were on a Standby Night Strike the day before. You can clearly see Vic's name in the top crew with F/Lt Perry as their Pilot.

Flying Programme 14th March 1941

On the 25th May it was decided that a nucleus of 206 Squadron was to form a new Squadron; 200 Squadron. Vic was one of those chosen to form part of the new Squadron and he made the journey with some other crew members by boat, as Vic was an Air Gunner he was requested to man some of the boats guns which he had never operated before. A total of 6 Hudson's left Bircham Newton for Gambia in West Africa via Gibraltar where they were for 3 weeks, at the time Vic remembers celebrating his 21st birthday. Whilst they were in Gibraltar some of the 6 Hudson's were used to escort Hurricanes to Malta, sadly some of the Hudson's and Hurricanes never made it and a large enquiry was raised about the loss of fighters and pilots, luckily for Vic he wasn't chosen for that particular job. Another sad loss was a large number of Ground Crew that had left for Gambia in a ship but sadly never made it.

Once in Gambia Vic shared a tent with 'Titch' who was married and from Nottingham, he was quite old at the age of 25!

1942

Vic's pilot was 'Pranger' Pritchett who was a short English chap and was a 2nd Pilot. Vic recalls an incident in January when they were taking off in a Hudson. 'Pranger' Pritchett was pilot, Vic and another chap Jones who was a South African were Air Gunner / Wireless Operators, Sgt Davis as Navigator and with them were 3 Army Officers. The plan was to get up in the air and survey the effectiveness of the Armies own camouflage. Hudson's needed a lot of speed to take off and even then the rudder control was not always the best, on this occasion 'Pranger' Pritchett swung on takeoff before making it off the ground. Needing to react quickly Vic had to push past the 3 Army Officers to force the door open and then virtually had to kick them out. Pritchett was able to make it out the front whilst the Hudson burst into flames, it had been an incredibly scary accident with the Hudson crashing into a number of different planes including a Blenheim and Vic remembers how quickly it burned. Thankfully all men made it out in time but it was to be the end of their crew as they were split up onto other aircraft.

1942 was to turn out to be a very busy year for Vic, on Monday morning on the 18th May, a crew of Sergeants took off on an operational flight in a new Hudson. Unusually there wasn't a 2nd pilot on board, instead a passenger; Met Officer Don Lloyd who occupied the 2nd Pilot's seat. They were in a Hudson that had recently arrived from England with the latest in Radio technology in it. It was a routine search, down to the equator and back again with enough fuel to last them 6-7 hours. They were following a similar flight path to previous Operations that Vic had been on, part way through it Vic noticed a glint from copper wires that hadn't been there in previous operations. Suspecting that something could be wrong around this area he moved down the plane to talk to the pilot. The Navigator had moved out of the nose to use the camera looking out for any unusual movements and it was at that moment that they heard a terrific bang. A shell had been fired from the ground and it had landed and exploded in the nose of the Hudson. The shrapnel had caused havoc with Vic and the Met Officer feeling the brunt of it as gallons of fuel washed into the cabin. Vic was injured in both legs but Don had been hurt more severely in his right leg with a piece of metal stuck in it.

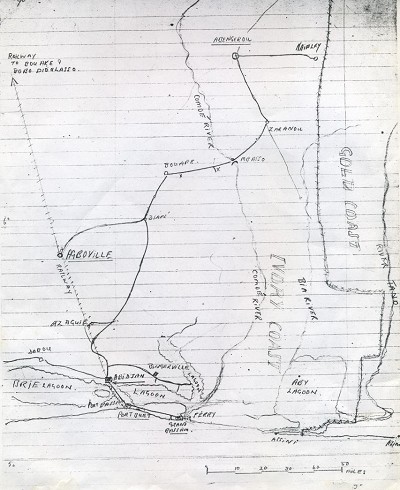

The Hudson's engines had stopped and so the pilot turned into wind heading towards the Gold Coast (Ghana), turning whilst in a glide was a dangerous manoeuvre but there was little alternative. They were very low down, which meant they couldn't bail out so the pilot managed to guide it down through shallow water and onto sand. The Pilot & Navigator managed to help Don out of the Hudson. All crew members had survived and the pilot came out of it without a scratch, luckily for him the instrument panels had completely shielded him from the blast.

Shortly after landing they realised they were in French colony territory that was controlled by the Vichy, it wasn't long before they were found by the local Vichy, pointing guns towards the Hudson they motioned to Vic to get out, who at the time was trying to send a message back to 200 Squadron. They were taken to a hospital at Abidjan where Don was seen to first, in the same afternoon they attended to Vic's wounds. A French man came in to see them and said "excuse my battery", at first Vic didn't realise what he meant but later understood he was apologising that his guns shot down their Hudson. Having operated on Vic and Don, the rest of the crew were able to visit Vic in his hospital room, they tied a number of sheets together and the 3 of them escaped by climbing out of the window, unfortunately they weren't free for long as they were captured within a few hours.

Having seen 1 escape attempt already the Vichy decided to move the 3 crew; Pilot, Navigator & second Wireless Operator up to Central Africa, which was within just 2 days of their landing. At this point they also decided to move Vic and Don into isolated rooms in a separate area of the hospital and it was during this time that Vic established that Don was a maths master. They were able to go into each others rooms and Don taught him Maths, English & French, it was a great way to learn as it was one to one tuition, many years later when Vic returned to the UK he passed all his exams.

3 months passed in the hospital and at every opportunity they pumped the staff about the local area and place names, arming themselves with as much local information as they could get away with. It was around September time that their plan to escape came to fruition. They had been taking quinine which were tablets for Malaria, Vic had requested an alternative tablet called mepacrin that were yellow in colour. Armed with the yellow tablets they removed the white edging material on their bed sheets and used the tablets to dye them a yellow colour. The French uniform was one similar to the plain RAF battledress shirts Vic and Don had on, but French Officers had yellow strips on their shoulders. Using their newly dyed strips of material they imitated the French Officers uniform and after spending 3 months monitoring guard shift changes they waited for such a change over. At the time there were religious celebrations in full swing and in the confusion they managed to walk out of the hospital, past a number of armed Vichy guards and into an Ambulance. It was about 8pm when they made their escape, they both jumped into the ambulance with Don at the wheel, they started it with a push of a button with no key required. Having previously pumped the hospital staff they knew which direction to take, taking the road parallel to the river they began the journey, it was a bumpy ride as most of the road was made up of loose wooden planks, having made it through a couple of villages they veered off the road and had to stop to get it back on the track. They then came across an army camp, at this point luckily no-one had noticed the ambulance had gone, Don having lived his early days in France spoke in fluent French asking for directions, after several hours they found themselves short of fuel, seeing the bush ahead of them they made for it looking to conceal themselves away, however the cover was quite deceiving as it didn't hide them. Within an hour of them stopping they were caught, they were taken back to the same camp where hours before they had asked the guards for directions.

Vic and Don were kept there for a couple of days until the Vichy organised transport for them by rail, it was at night when they left and they stopped at one place under full guard, they spent another day traveling still under guard then they turned westwards and spent 3 days crossing several rivers all under full guard. They finally arrived at Bamako where they were placed in prison. On the edge of the prison barracks there building that had been a modern school used for training agriculture and had 2 large classrooms. There was around 25 NCO's and Vic found himself as the only F/Sgt and hence was the senior Sgt, there was also 1 Naval man and 1 civilian pilot that had been dressed as a Squadron Leader. As he wasn't actually a Squadron Leader it meant Don was the highest ranking Officer amongst them. A few weeks prior to Armistice day (11th November) on a Wednesday Vic had spotted a Hudson, he noticed it was a military one as he could see the turret, Vic and Don decided to try their luck and move out of the prison grounds to conduct a trip around the town, without disguise they managed an hour or so and made it back without been spotted or missed, this gave them a good idea of the layout of town. A week or so later Vic rounded everyone up for a parade for Armistice Day, unbeknown to them Operation Torch had commenced 3 days earlier on the 8th November. Once it was clear that the Allies were taking a foothold in North Africa, the French people in Bamako let them move freely in the town. Here's a map Vic had put together about his capture route that was kindly provided by his son John in Feb 2014.

1943

Command had soon changed over to De Gaulle and transport by train was laid on for the 40 to 50 men. When they got onto the train they found themselves with many other British men such as other captured pilots or Navy personnel. Instead of going onto Dakar it stopped short as the last part of the line ran parallel to the Gambia. They made it off the train and onto a boat that took them down to Bathurst, amazingly this was just 15 miles away from 200 Squadrons base and so they rejoined the Squadron. He had spent around 7 months away from the Squadron in total. Although Vic was back on 200 Squadron they advised him to remain with the other internees and to go down to Sierra Leone where Don Lloyd also went. There Vic spent about a month on Catalina's before making his way to Scotland by boat.

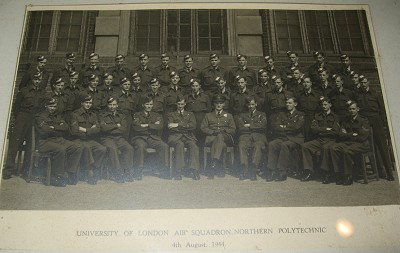

Once back in the UK Vic joined the University of London Air Squadron.

It was around Christmas that he proposed to Dorothy.

1944

It was around Christmas the following year that Vic married Dorothy Hilda Juggins.

University of London Air Squadron

4th August 1944

Vic is sitting down 5 from the left

Vic is on the front row 2 from the left

1945

tbc...

2008

2008 was a sad year for Vic as he lost his wife Dorothy on the 8th April at the age of 86. She had known Vic from childhood and he often talks about her.

2009

On the 30th April F/L Vic Reynolds received an Air Officer Commanding (No 22 Training Group) commendation. It was awarded for all the years he put into the Air Training Corps as a whole. He was presented the commendation by Lord Lieutenant of Staffordshire, Mr James Hawley. Vic is the ATC's longest serving CI and former Commanding Officer.

F/Lt Vic Reynolds & Lord Lt James Hawley

30th April 2009 at the Stafford Civic Building

2010

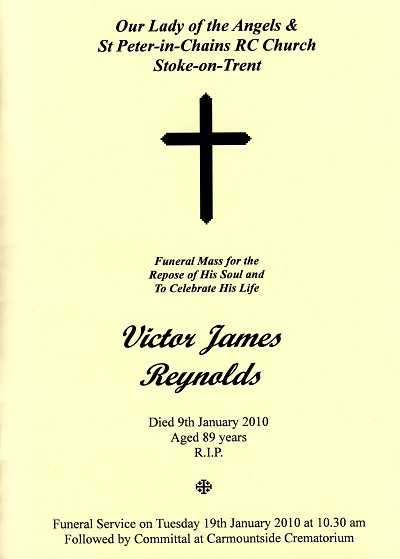

In the early hours of Saturday morning on January 9th Vic sadly passed away, the funeral was held at Stoke RC Church in Hartshill. I have lost a great friend!

Stoke-on-Trent Wing Commander Colin Cope RAFVR(T) Ret'd sent over the following details about Vic.

Flight Lieutenant Victor James Reynolds (Vic)

There can be few people involved currently with the Air Training Corps whose Royal Air Force Service pre-dates the Corps' formation by several years but one such remarkable person is Victor James Reynolds.

Victor or Vic as we all know him joined the Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve in June 1939 and trained as a Wireless Operator and subsequently an Air Gunner. He saw active service with 206 and 200 Squadrons, was wounded and imprisoned by the French Vichy. On return to the UK, Vic continued his service until 1950 when he was demobilised and placed on the reserve for another 4 years.

In 1954, Vic began his formal and long association with the Air Training Corps and assisted with several units in the Staffordshire Potteries before being appointed Adult Warrant Officer in July 1959 and commissioned as a Pilot Officer in the Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve (Training) Branch in 1960. Following some 21 years of uniformed service, Vic retired in 1981 holding the rank of Flight Lieutenant, and immediately became a Civilian Instructor, an appointment he continued to hold 55 years after his first appointment.

In an addition to more than half a century of dedicated and exemplary service with the Air Cadet Association Vic has made an exceptional contribution to the development and training of many hundreds, if not thousands of, cadets and other personnel in all areas of the field of radio and wireless telephony and high frequency communications. He has been the Wing Signals Officer and controller of the whole Air Training Corps radio network. His enthusiasm and great knowledge of communications systems and procedures are probably without equal in the Corps and unlikely to be surpassed. His teaching of radio and other subjects has inspired young people to develop further their interest in communications and air mindedness.

Vic is greatly respected by all who knew him and is a legend in his own lifetime. His long and distinguished service, coupled with his unstinting efforts for generations of air cadets he has taught, nurtured and encouraged, is deserving of the highest accolade.

R.I.P Vic - We have lost a great friend and college in your passing

Wg Cdr Colin Cope RAFVF(T) Ret'd

Hon Vice President

Staffordshire Wing

Air Training Corps

10th January 2010

Investigation

I researched the official archives I had on 206 Squadron and found 14 Operational Logs where Vic was mentioned, I have listed them all below. In doing so I established links with Vic and two Pilot Officers that he flew with on the 10th February 1941, they have their own stories within the 'Memoirs' pages:

-

Maurice Warren's story is within the 'Pilots: Part I' section

-

John Waterman's story is within the 'Pilots: Part II' section

206 Squadron Operational Logs

9th Jan 1941: ? 04:35 to 08:25

Crew: F/Lt Perry, P/O Kennan, Sgt Stibbons, Sgt Reynolds

12th Jan 1941: Raid 13:30 to 15:50

Crew: F/Lt Perry, P/O Kennan, Sgt Stibbons, Sgt Reynolds

15th Jan 1941: Search 09:05 to 12:05

Crew: F/Lt Perry, P/O Kennan, Sgt Stibbons, Sgt Reynolds

17th Jan 1941: Raid 12:55 to 15:25

Crew F/Lt Perry, W/C Roberts, P/O Kennan, Sgt Stibbons, Sgt Reynolds

27th Jan 1941: Patrol 05:45 to 07:55

F/Lt Perry, P/O Kennan, Sgt Stibbons, Sgt Reynolds

30th Jan 1941: Patrol 06:05 to 10:25

F/Lt Perry, P/O Kennan, Sgt Stibbons, Sgt Reynolds

10th Feb 1941: Convoy 10:15 to 13:00 (1 day before Waterman failed to return)

P/O Warren, P/O Waterman, Sgt Hannah, Sgt Reynolds

18th Mar 1941: Local Flying 11:10 to 12:10

F/Lt Perry, P/O Webb, A/C ?, Sgt Reynolds

18th Mar 1941: X-Country 13:10 to 15:25 (2 days before Warren crashed Hudson)

P/O Bull, P/O Kennan, Sgt Gibbs, Cpl ?, Sgt Reynolds

29th Mar 1941: X-Country 12:40 to 15:40

F/O Burne, Sgt ?, Cpl ?, Sgt Reynolds

1st May 1941: X-Country 10:35 to 12:45

P/O Webb, P/O Humphrey, Sgt Swain, Sgt Smith, LAC ?, Sgt Reynolds

7th May 1941: Patrol: 01:45 to 04:30

Sgt Gibbs, Sgt Turnbull, Sgt Coldbeck, Sgt Wiesman, Sgt Reynolds

7th May 1941: X-Country 10:00 to 10:20

Sgt Gibbs, Sgt Turnbull, Sgt Coldbeck, Sgt Wiesman, Sgt Reynolds

16th May 1941: X-Country 11:10 to 13:05

S/L Hennock, P/O Hayston, P/O Kennan, Sgt Coldbeck, Sgt Smith, Sgt ?, A/C Holyroyd, Sgt Connor, Sgt Reynolds

This ties in with Vic's move from 206 Squadron to form 200 Squadron on the 25th May 1941. Ken (Grandad) arrived with 206 Squadron less than 3 months later on 10th August 1941.

Jack Farley

Rank: Flight Lieutenant

Number: ?

Joined 206: ??/03/1942

Flew with Ken: 0 times

Born: ??/07/1922

Died: Lives in England

I first came across F/Lt Jack Farley by reading his name in the 206 Squadron book 'Naught Escape Us' by Peter Gunn, I then found his story on the BBC Website. In September 2008 Jack kindly agreed for that same story to be included here along with some additional information and photographs he sent over to me.

The first photograph below was provided by Des, one of Jack's sons. It was taken in 1945 and was sent over after we met at the 206 Squadron Association Reunion in April 2010.

F/Lt Jack Farley

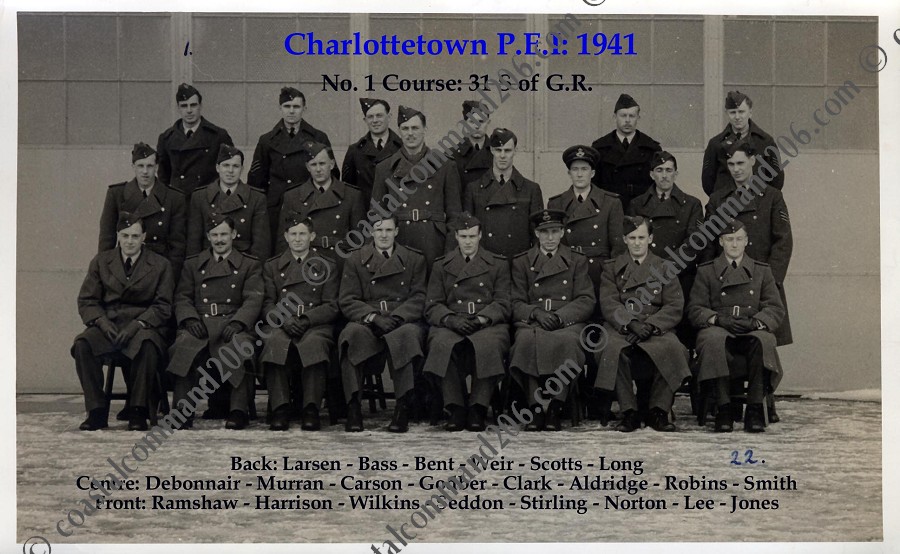

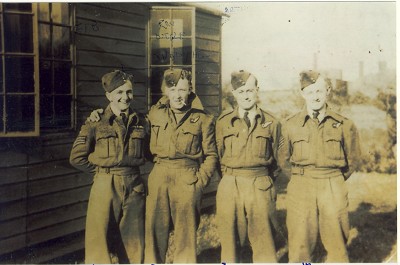

The photograph below is from the early days in the OTU at Silloth where a number of people in this section completed their final training, including Ken.

Crew OTU Silloth

End of 1941 / Start of 1942

Gib Whittamore (Pilot) - Ron Diggle (WOp/AG) - Arthur Griffiths (Navigator) - Jack Farley (WOp/AG)

Here is a fantastic photograph of Jack and his fellow crew members just before they embarked on the 3rd 1,000 Bomber Raid. 12 Hudsons from 206 Squadron joined this raid, the crew below was one of those and Ken was the pilot of another, the Hudson that Jack was in for the raid was AM785 'C'. I wonder whether a crew photograph exists of Ken and his crew before the raid?

Bremen 1,000 Bomber Raid Crew

25th June 1942

A Brown (Navigator) - Jack Farley (WOp/AG) - Stan Weir (Pilot) - Powditch (WOp/AG)

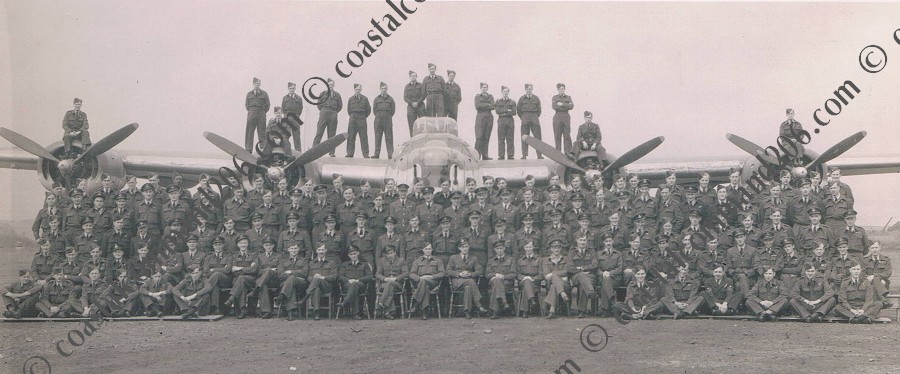

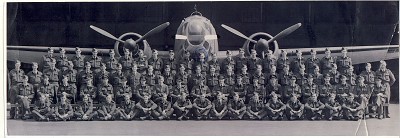

Here is a group photograph of 206 squadron that Jack supplied me. I cannot find Ken on here so it could have been taken when he was on some leave. It was taken in Aldergrove in 1942 (April / May)

206 Squadron: Aldergrove 1942

Jack Farley - Top Row, 11th from left

F/Lt Jack Farley's Story

Here is Jack's story that is also hosted on the BBC website at:

http://www.bbc.co.uk/ww2peopleswar/user/45/u539345.shtml

Early Days

At the outbreak of World War Two on Sunday 3 September 1939 I was working as a clerical officer at a hospital in Ashton-under-Lyne, Lancashire, where I lived with my family. Like any normal person at that time I wanted to fight for my country and as soon as I turned 18-years-old in July 1940 I volunteered for the Royal Air Force.

I wanted to join the RAF because they were the only service that seemed to be having an effect. The army had just retreated from Dunkirk and the navy had not won a significant battle since the River Plate months earlier. The RAF, however, were running nightly bombing raids on Germany to wear the enemy down.

In the summer of 1940 I reported for active service at RAF Padgate near Warrington, Lancashire. One of my first memories of Padgate is sitting down to dinner and being served a piece of fish with the bones still in it. I couldn't believe it, this sort of thing never would have happened at home. From then on I realised that my life was going to be very different from my first 18 years but I was proud to wear the royal blue uniform of the RAF and I was proud to be serving my country.

After being kitted out at Padgate I was posted to RAF West Kirby in Wirral, Cheshire, for basic training where I learned how to march, salute and operate a rifle. Before long I was given another stark reminder how different military life would be from my civilian days, when I failed to salute a passing officer.

Before I had even realised my mistake two RAF policemen had hauled me in front of an imposing 17-stone adjutant and I was being asked to explain myself. In all honesty I hadn't seen the pilot officer walking past but I certainly wasn't going to admit this. Instead, I said that a boil under my arm made it too painful for me to salute. Luckily the adjutant believed me but I from then on I knew that if I wanted to have a long career in the RAF I should pay more attention to its rules and regulations.

Several weeks later I was posted to Blackpool for three months for my initial wireless training. Upon arrival I was billeted to a private house with another airman. I was pleased that I was going to have some company - until I discovered that I was expected to share a double bed with him. After we both strongly objected we were moved to another billet where, thankfully, we had a bed - and a room - each.

I enjoyed my time in Blackpool. At 8am every weekday morning all the new trainees assembled at the Olympia building for Morse Code training. I was a quick learner and soon reached the required 12 words per minute. I also enjoyed spending many off-duty weekends on the pleasure beach.

One weekend just before the course ended, however, I decided to go home and see my family, even though we were forbidden from leaving the town. My father had been ill in hospital for some time suffering from leukaemia and I got it into my head that I had to visit him. I left for Ashton-under-Lyne on Friday and returned on Sunday night to face disciplinary action. Although I had broken RAF rules I did not regret what I did for that was to be the last time I would see my father alive. He died two days later at the age of 46.

When I saw him in the hospital he knew he was about to die because he asked me, as his eldest son, to take care of the family. However it was nearly two-and-a-half years before I would see my mother, my sisters Molly, Margaret and Desmo and brother Leo again. In December 1940 I was posted to RAF Yatesbury in Wiltshire for the final part of my training to become a wireless operator.

As well as learning advanced Morse Code at Yatesbury, I also remember enjoying excellent food there. While I still had to take the bones out of my fish, we often enjoyed delicious meals of Harris's sausages because the factory was only a few miles down the road.

I completed my course in March 1941 and was then awarded my sparks badge. I was a qualified wireless operator, earning 28 shillings (about £1.40) a fortnight. I then spent a short time doing general duties in RAF Detling, Maidstone, Kent, while I waited for my air gunner's course.

Until then I hadn't minded moving around the country so frequently because I enjoyed seeing new places. However, when I was posted to south Wales only weeks later I was very disappointed.

Often on the weekends I would go to local dances in Tonbridge. One Saturday night I saw a very attractive girl and was lucky enough to partner her after excusing an army private during an excuse me dance. We got on very well and I had high hopes for us so arranged a date for the following Saturday.

A few days later, though, I was sent to Number 1 Air Gunner School at Pembrey, Llanelli, south Wales, and I had no way of contacting the girl. I never saw her again and I used to wonder what happened to her and if she ever ended up with that army private.

I did not have time to dwell on it though for six weeks later I was awarded my air gunner's brevy and sergeant's stripes and my pay increased to 9 shillings (about 45p) a day. I was now a qualified wireless operator air gunner (wop/ag).

The final part of my training before being posted to an operational squadron was at Operational Training Unit (OTU) Silloth, near Carlisle, in Cumbria, where I arrived late December 1941. Here I joined a crew of three alongside Gib Whittamore (pilot) Arthur Grifffiths (navigator) and Ron Diggle (wop/ag) manning a Lockheed Hudson twin-engine bomber.

We all came from very different backgrounds; Gib was a native Canadian, Arthur came from Wales and Ron was the grandad of the crew - 23-years-old and already married! But we all had the same outlook on life and bonded very well.

We spent a lot of time together, taking part in night flying and low-level practice bombing exercises over the Solway Firth in Scotland. And although there were several fatal accidents during the course of our training we escaped unhurt. A close friend of mine Ginger Taggart, however, was not so lucky. He and his whole crew died the day before the end of the course when his aircraft crashed into the sea.

This experience brought home to me the fact that my future was an uncertain one to say the least, but it made me more resolute to serve my country as best as I could. In March 1942 my crew was posted to 206 Squadron, Aldergrove, Northern Ireland, where I began operational duties.

206 Squadron Life

On arriving at 206 Squadron, my crew were split up and my navigator and myself formed part of Flight Lieutenant (F/Lt) Goddard's crew. We conducted patrols over the Atlantic including convoy patrols and anti-submarine searches.

On one of these patrols we had to take a barometric pressure reading at about 50 feet above the sea. Whilst we were doing this, our engines suddenly seemed to lose power. We made it back to base all right, only to find that F/Lt Goddard had forgotten to switch onto the main fuel tank from the overload tanks soon enough.

It may have been an easy mistake to make but it shattered my trust in F/Lt Goddard and I was annoyed that he had put us in such danger. Soon after this incident Arthur and I moved to join another crew and only days later F/Lt Goddard's crew had a fatal crash. There were no survivors.

Next I joined Stan Weir's crew with Stan as pilot, Brown as navigator and Powditch as wop/ag. My dear friend Arthur was posted away to join another squadron.

One day I was asked to fly with a new pilot who had recently joined the squadron for local flying practice. At the end of the exercise as we touched down on our landing he failed to allow for a strong cross wind and the aircraft left the runway and crashed. Fortunately neither of us were injured.

Later on that year, I was again involved in another near miss when I was on a flight from Aldergrove to RAF Jurby, Isle of Man, to pick up aircraft spares and refreshments for the forthcoming St. Patrick's celebrations.

As we were taking off to return to base I happened to look across to the port wing and notice that fuel was streaming from the wing tank. I touched the pilot on the shoulder and pointed to the wing and he pulled back on the stick and aborted take-off. Apparently the maintenance personnel at RAF Jurby had not replaced the fuel cap.

At the time, I remember thinking that with our own men making such serious mistakes, I would be lucky to come out of the war unscathed.

Thousand-bomber Raids

On the 25 June 1942 my Coastal Command crew was one of 12 to take part in the Thousand-bomber Raids on Bremen - a joint operation with Bomber Command and Training Command.

Before leaving Aldergrove for North Coates, Lincolnshire, all personnel had to paint the underside of their aircraft black in preparation for the night-time operation.

Arriving at North Coates, we found that there was no space for us because there were so many aircraft already stationed at the aerodrome from other squadrons taking part in the operation. We were then instructed to fly to a satellite airfield named Donny Nook where all personnel, from commanding officers to maintenance workers, had to sleep on camp beds in a large marquee.

The following day all 12 crews attended a briefing at North Coates. The operations room was so packed with personnel that I had to stand on top of a radiator. I remember the words spoken by the group captain, station commander, as clear as if it were yesterday: "It has been decided to obliterate Bremen".

206 Squadron was to spend nine minutes over the target area. On crossing the Dutch coast, we encountered heavy anti-aircraft fire that continued all the way to Bremen. We arrived over target at 12.54am and observed vast fires that had been started by an earlier waves of bombers.

We flew at 18,000 feet, the first time ever I, and the rest of the crew, had flown at this height and it was the first time we had needed to use oxygen. Our normal operational height was 4,000-5,000 feet.

On approaching Bremen I began to worry that the four engine bombers would drop their bombs on us from a greater height but this did not happen.

A few minutes later were we above the target and we released out bomb load. Devastation was immense - the whole target area was a mass of flames.

Then, we were just turning to head home when out of the darkness came a German night-fighter that tried to shoot us down. Several minutes later he was nowhere to be seen, but our worries were not over, for our pilot announced: "Only fifteen minutes fuel left and there's no sign of our coast line."

For the next ten minutes there was silence in the aircraft and we all held our breath. By the time we landed at North Coates there was only five minutes of fuel remaining.

The damage to our aircraft was mainly from shrapnel from exploding anti-aircraft shells, but we counted ourself lucky because we lost three aircraft out of 12 during the sortie. Two were over the target area and the third, containing the commanding officer and his crew, crashed in the sea near the coast. Their bodies were washed ashore three weeks later.

206 Squadron was due to bomb Hamburg the next night but this was cancelled due to the number of heavy losses sustained on the Bremen raid. The total loss for Coastal Command, Bomber Command and Training Command was 51 aircraft.

July saw the squadron move to Benbecula in the Outer Hebrides, and we converted to B17 Flying Fortresses that gave us longer hours on patrol over a larger target area. Shortly after this, I was posted overseas to be a wireless instructor to a newly-formed OTU, 65 miles south west of Alexandria, Egypt, in the desert.

75 OTU

The journey from Avonmouth, Bristol, to South Africa took nearly six weeks. During that time I had to man an anti-aircraft gun post position on board the troop ship with an airman as ammunition loader.

At Clarewood Transit Camp near Durban we slept under canvas for six weeks before boarding a former enemy liner which took us to Egypt. During our time in the camp we were offered great hospitality by the local civilian population who invited many of us to their homes for meals and loaned us their cars.

We arrived at Port Tewfik in early December 1942. We then travelled north to Suez and on to an RAF base in the desert called Gianaclis, some 40 miles south-west of Alexandria, where we established 75 OTU.

It was while I was with OTU I had another narrow escape from a serious accident. On one training exercise our Avro Anson aircraft was due to stage a mock attack on a royal naval submarine just off the coast off Egypt.

While I was in the process of instructing a trainee how to send a sighting report, the aircraft suddenly filled with smoke.

The pilot, who had recently joined the OTU from a Beaufighter squadron, had to fire the colours of the day so the submarine could identify us. However, instead of opening his port window to fire the pistol he fired it through the floor of the aircraft.

The exercise was immediately aborted and we returned to base to discover a square metre of the port wing which joined the fuselage had burned away, just inches from the fuel line. If that line had been hit, the aircraft would have blown up and we would all have been killed.

There was one fatal accident while I was at the OTU; one of the training crew crashed into the sea on a night flying exercise. The bodies were recovered later and given a military funeral in Alexandria and the instructors, including myself carried the remains.

During my year as an instructor there was a certain amount of unrest amongst UK ground personnel at the camp. On one occasion the station flagpole was chopped down. No-one owned up to the act and as a result we were all confined to camp for one month with no leave to Alexandria.

The second occasion of unrest occurred when a visiting party gave a concert at the base. At the end of the show, as the group captain gave them a vote of thanks, his speech was drowned out by boos. I thought it was disgraceful for those responsible to show such discord in front of civilians while war in the Middle-East was continuing.

The third instance of misconduct at the camp involved the adjutant, who got so drunk one evening that he cancelled night-flying. When the wing commander found out he placed the adjutant under arrest, he was court marshalled, reduced to the rank of a non-commissioned officer and posted elsewhere. Later on the group captain was also posted away due to his inability to control men.

Towards the end of my year as instructor I received my commission as a pilot officer and was posted back on operations to 221 Squadron Malta, a Wellington torpedo squadron. I was not sorry to leave 75 OTU. It was such an unhappy camp.

221 Squadron

On arriving at 221 Squadron I became a member of Pilot Officer Keegan's crew. Our task was mainly anti-submarine patrols and air reconnaissance. Later I joined Wing Commander Mike Shaw's crew until his tour was completed and he was posted back to the UK.

Once again I thought my number was up whilst I was on patrol off the toe of Italy one day on an anti-shipping patrol. I thought the navigator said "it's windy" when he was actually saying "dinghy". We were in severe trouble - our engines had started to loose power and we were steadily dropping from our patrol height of 5,000 feet towards the Adriatic Sea so I sent an SOS

Suddenly the operational radio frequency went quiet. I heard RAF Gibraltar calling asking what the trouble was, followed by RAF base in lexandria and my own base in Malta, RAF Luqa, asking me the same question.

By then we had started our ditching drill and had the emergency dinghy to hand - we were convinced we were going into the sea. Then, when we just a few hundred feet above the water, the power slowly started coming back to our engines.

The cause of our problem was due to the fact that the second pilot had not switched onto the main tanks from the overload tanks earlier, just as F/Lt Goddard had forgotten to do several months earlier. Once again, I had escaped serious injury.

Shortly afterwards, in February 1944, my squadron moved from Malta to Grottaglie near Tarantino, Italy, where we shared the airfield with an American bomber squadron. Our task was now to bomb anti-submarine pens on port installations along the Yugoslav coast and across northern Greece, Albania, and Italy.

We also had to assist Tito who was head of the Yugoslav Partisans. He had assembled a force on the Island of Vis to attack a nearby island which was held by the Germans and our job was to bomb E-boats so Tito's craft could land there. It was during one of these bombing raids in the northern part of Yugoslavia that I had another brush with death.

One day as we were crossing the Adriatic Sea I noticed two large exhausts of an aircraft dead astern which I quickly identified as a Beaufighter aircraft: one of our own. The next few seconds though, I could not believe my eyes. The night-fighter had lowered his flaps and opened up with four cannons and six machine guns.

I was positioned on the rear gun but I did not return fire because I assumed the Beaufighter would soon realise he was attacking a friendly Wellington bomber, not a German aircraft.

After a minute or two the fire stopped and there was no longer any sign of him so I assumed ground control has warned him he was attacking a friendly aircraft. Furthermore, we had aleady fired the colours of the day and our bomber was also fitted with IFF: Identification Friend or Foe.

A few moment later, however, and the Beaufighter returned for a second attack. Once again I did not return fire and we somehow we managed to stay up in the air. At this point I decided that if the bomber were to return for a third attack I would have no option but to return fire. It would be him or us.

Thankfully he did not come back again and we eventually made it to Grottaglie. Our pilot managed to do a skilful ground loop and we landed just 70 yards from an American bomb dump. With cannon shells through the props, no port wheel, part of the port wing and main fuselage shot away and a broken air speed indicator it was nothing short of a miracle that we escaped uninjured.

Shortly after the incident a court of enquiry was held. The Beaufighter crew had assumed that our Wellington had been captured by the Germans and was about to attack a target in Italy. For the Germans had recently made a surprise attack on Allied shipping at the Port of Bari on the Italian coast and had sunk over forty ships.

But because we did not release any bombs, nor return fire on the Beaufighter, the crew were severely reprimanded over the incident. Once again I had stared death in the face, and somehow managed to survive.

This incident was to be one of my final experiences of operational duties for just a few weeks afterwards, on August 1 1944, I was posted to a transit camp in Heliopolis, Cairo, to await my next posting.

Final Days

After a few weeks mainly censoring airmen's mail, I learnt that instead of being posted to South Africa where I had applied to be an instructor, I was being sent back to the UK. In October 1944, after nearly two and a half years abroad, I disembarked at Liverpool and began three weeks leave.

After months in the desert I was amazed at the green fields, and was shocked to find the weather was so bitterly cold. I reached my home in Ashton-under-Lyne and knocked on the front door, but just when I thought the longing to see my family would be over, I discovered they were all out.

My mother had gone on holiday to visit family in Belfast, my youngest sister Desmo was at work, my other sisters Molly and Margaret were away with the WRENS and my brother Leo was at sea with the Navy.

I didn't have a key to the house because so many years had passed since I was last home so I went to the hospital where I worked before the war and visited some of my former colleagues. A few days later I went to Belfast to see my mother and relatives.

On completion of my leave I spent a few weeks at RAF Brackla, a few miles outside Inverness, Scotland, where I awaited my posting. I was soon sent to RAF Hendon, London, and joined Transport Command where I became a signals briefing officer.

Shortly afterwards I went to RAF Lyneham, Wiltshire, and I travelled to Cairo, Sharjah in the Persian Gulf, Karachi in Pakistan, Maribor in India and Ratmalana, Ceylon. My job was to confirm the signal information given to wop/ags was correct and up-to-date and teach them what frequencies and call signs to use.

By this time I had become tired of flying so I didn't mind that I was no longer on operational duties. A few months later I became a signals briefing officer at RAF Merryfield, Somerset, and finally I was sent to RAF Holmsley South near Christchurch, Hampshire, where I stayed until my release from the service on July 6 1946.

At the end of the war I returned to Ashton-under-Lyne and took up my old position at the town's hospital. If the war had not taken place I would have probably been manager by this time, but I has to start at the bottom of the ladder once again.

A few months later, however, I was forced to resign from my post and take over the running of a family hotel in Belfast after the death of my great aunt. I then began my long career in hotel management.

My time with the RAF was a great experience and I was very proud to have reached the position of flight lieutenant by the time I left. When I was with the force I saw countries I never would have otherwise seen and I met people of cultures I never would have normally encountered. I also made many friends, two of whom I am still in contact with.

I regularly telephone former navigator Arthur Griffiths who now lives in Newport, south Wales, and I last visited Gib Whittamore, former pilot and navigator, in Canada in 2001. However, my war-time experience is not one I would wish to repeat. I had six near fatal accidents during my time in the service, none of which were due to enemy action.

Flight Lieutenant (Jack) H D Farley RAF VR

206 Squadron and 221 Squadron

Coastal Command

I would like to dedicate this story of my service career to all RAF wireless operator air gunners in recognition of the valuable work they did as important members of bomber crews.

Bill Blackwell

Rank: Sergeant

Number: ?

Joined 206: ??/02/1943

Flew with Ken: 0 times

Born: ??/??/19??

Died: ??/??/????

The following information was supplied in May 2008 by Bryan Yates who is a researcher of RAF Flying Fortresses, his computer hard drive crashed some years ago which unfortunately meant he lost the contact details of the supplier of Bill Blackwell's story. After reading the extract I felt it was closely linked to 206 Squadron and the other people mentioned on the site, and so I've published the information below. I'd be very interested to hear from anyone that has links to Bill and it would be great to add some photographs of him in this section. Below is the extract that Bryan sent over, Robert Stitt contacted me in September 2008 with a couple of corrections to the text.

Bill Blackwell started his RAF career with number 407 squadron flying Hudson's, later moving to number 280 squadron, this time flying in Anson's on Air Sea Rescue duties. In February 1943, Bill was posted to number 206 squadron at Benbecula in the Outer Hebrides, were he flew the B-17E or Fortress 11.

Here, as an air gunner, he encountered the ball turret for the first time. Bill remembers it well, he says. 'It was a frightening experience on your first encounter, I remember my first trip in a Fortress ball turret. We all did a two hour stint at each station, you sat like a baby in your mothers womb, and the controls were not as stable as the other turrets. You could soon find yourself upside down, and if you rotated to fast you could spin round. I think we were all glad when they became obsolete in the RAF Fortresses.'

Of the other turrets Bill recalls, 'The mid-upper was a very good turret, well armed with .50s and easy to control. The tail position was also very acceptable, you had to crawl in on your hands and knees to enter, then you knelt with your bottom on a bicycle seat'. He remembers one trip flown in bad weather particularly, 'we were on patrol and the cloud base was down to 500 feet, we obviously had to fly below that to see where we were going. The cross wind was blowing the tail with such ferocity, that I was continually thrown from side to side, banging my head on each side of the fuselage. I could do little about the situation and had to suffer it, quite a painful experience'.

He arrived as a replacement crew member, so had no regular crew at first, so his first trip was as a spare bod with F/Lt Roxburgh and his crew. They took off from Benbecula at 08:05 hours on the 20th of March 1943 in F-Freddie on a convoy patrol, the rendezvous with the convoy was in mid-Atlantic and the patrol lasted for ten and a quarter hours.

Bill again flew with this crew on the 25th of March, leaving the windswept base of Benbecula at 04:45 hours and heading out into the Atlantic. Where they were to sink U-469, commanded by Oberleutnant Emil Claussen off the south east of Iceland. The same aircraft FK195 'L' with a different crew would sink yet another U-Boat a short time later, while damaging a third while still with 206 Squadron.

Bill was to fly one more sortie with this crew before they finished their tour, that was on the 30th on a anti-submarine sweep. He did not get on to well with this senior crew, often an established crew did not like a 'Sprog' member near the end of their tour as this was considered unlucky.

However, he was soon remustered into a new all NCO crew, Sgt Gullen the pilot, was a large man six feet five inches tall, and very likable as were the rest of the crew. They got on well together on and off the ground, and they were to stay together as a crew from April 1943 to February 1944, when Bill finished his tour. The new crew spent most of April in training, flying navigation trips and decent through cloud exercises. Then finally they began operational life, as a Coastal Command crew. On a typical sortie the crew would be woken at some ungodly hour by a not to sympathetic NCO, they would then have the RAF standard pre-flight meal of bacon and eggs, not an ideal choice if the stomach was not up to par.

Then the briefing would take place, the convoy number the number of ships in the convoy, and details of the escorting vessels. After this the radio operator would be given the codes for the day, and the navigator would collect all the necessary charts for the patrol. Bill always carried a black box with him when he flew in case he ever got shot down, in it were boiled sweets, maps, Varey cartridges and a pen and paper. Two pigeons were also carried on the aircraft in special containers, but they were never used to Bills knowledge.

Their first operational sortie was on the 27th of April 1943 in Fortress A-Apple, it was a anti-submarine sortie using the Creeping Line Ahead (CLA) search pattern, and the next four months were to be spent on similar operations. One patrol was in search of a damaged U-Boat, but they did not make contact with it, they also took part in the search for a missing Sunderland without success, the longest patrol undertook by the crew was 11 hours 50 minutes.

Then on the 5th of October 1943, the crew boarded their Fortress 'Z' and took off at 09:45 hours leaving the inhospitable Benbecula airfield and headed for Thorney Island where they arrived at 14:30 hours, this was to be the first stage of their trip to Lagens in the Azores.

They did not leave Thorney Island until the 20th on the next stage of their journey this time flying H-Harry, they lifted off at 13:35 hours in transit for St. Morgan. On the 23rd of October they took off again, this time on the last leg of the flight, heading for Terciere in the Azores. They were the second aircraft to land on the new and unfinished airfield, and soon appreciated the mild climate after their sojourn in the Outer Hebrides. With no blackout and the town bars open all day, they also came to appreciate the neutral status of the island.

On the 13th of December they took off at 09:00 hours in H-Harry on an anti-shipping sweep, they were searching for a surface raider disguised as a neutral freighter. On one occasion they thought that they had found it, but it turned out to be a simple mix up in translation while talking to the crew of a genuinely neutral vessel. They were also down to fly on Christmas Day, the 25th of December was just another day in Coastal Command. They were to fly a patrol to the Bay of Biscay, in search of some German destroyers trying to make for the port of Brest. The only vessel sighted that day was HMS. Sheffield which they photographed, as it was also looking for the German raiders.

The photos were sent to the crew of the ship at a later date, on return to Lagon the crew were to discover that they had missed their Christmas dinner. When they inquired at the field kitchen as to the whereabouts of their Christmas fare, they were informed that all the dinners had gone and that they would have to be happy with steak and kidney pie.

The Fortresses were usually fitted with a Bendix type crystal controlled wireless set, it was very easy to use and all the crew took turns logging the specifically timed signals. The radio operator would also have to listen out for instructions such as call signs etc... Bill remembers the Fortress Radar sets well, 'the Radar was quite updated from my last squadron, it was the full scan type with a 360 degree rotation and with a range of 100 miles. The effective range for picking up a U-Boat was about 10 miles, but it was possible to extend this to 25 miles in some conditions'.

On the 31st of January 1944, Sgt Bill Blackwell was posted to Aldergrove, Northern Ireland having completed his tour, and that is were his contact with the Fortress ceased.

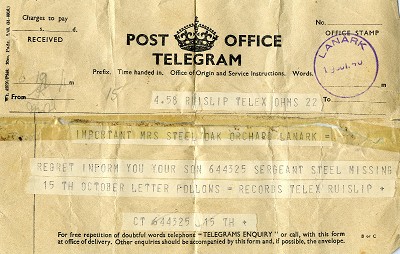

Jim Steel

Rank: Flight Sergeant

Number: 644325

Joined 206: 13/05/1940

Flew with Ken: 0 times

Born: 20/07/1920

Died: 15/10/1940

I first came into contact with David Cotterill when he e-mailed me after reading the site. He was in the process of researching his Uncle Jim Steel. Jim had served in 206 Squadron from May to 15th October 1940, when he was killed whilst on patrol in a Hudson. Dave subitted the following words and pictures on Jim...

"A picture of my uncle Jim had always hung on the living room wall, it was known that he had been a gunner in a bomber and it was believed that he had been shot down over Holland. As a result of coming across the CWGC website in 2005 I decided to try and find out more about him. After obtaining his service record, making numerous trips to the National Archives and investigating many other sources I built up a pretty comprehensive picture of his service in the RAF during 1940, what follows is a brief summary.

Jim Steel joined the RAF in 1939 at the age of 18; after training at Cardington, Evanton and Silloth he was posted to 206 Squadron on 13th May 1940 as a wireless operator/air gunner (WOp/AG). At the time 206 Squadron was based at Bircham Newton in Norfolk and was equipped with Hudson aircraft, this was a twin engine commercial aircraft built by Lockheed which was modified to enable it to fulfil a reconnaissance and bombing role. The Squadron's main task was monitoring the enemy's invasion preparations by flying so-called 'SA patrols' over the North Sea, it also carried out attacks on enemy-held ports and shipping. The summer of 1940 was a busy period for 206 Squadron; the evacuation of the allied armies form Dunkirk would take place 2 weeks after Jim arrived on the Squadron whilst the Battle of Britain would commence on 10 July. Jim carried out a total of 19 operations, the more notable ops are described briefly below:

Notable Op's

20 Jul 1940 - bombing raid on oil storage tanks at Gand, Belgium

27 Jul 1940 - bombing raid on oil storage tanks at Amsterdam, unable to find the target so bombed canal and railway intersection at Zijkanaal

14 Aug 1940 - SA4A patrol, Jim was in Hudson N7401 which crashed and burned out shortly after takeoff and all other crew members killed. Incredibly, Jim sustained minor injuries and whilst recovering from them 'Flight' magazine visited Bircham Newton on 3 Sep and published an article about the Squadron on 17 Oct. The article featured Hudson V-VX, the aircraft in which Jim would lose his life. After 2 weeks sick leave Jim was back in the air

21 Sep 1940 - patrol close to Dutch coast (SA4C). Attacked 7 enemy minesweepers with two 250lb general purpose bombs and one 250lb anti-submarine bomb and claimed one near miss

25 Sep 1940 - patrol off Dutch coast, attacked and sank large German supply ship

15 Oct 1940 was Jim's final operation. The pilot was rugby international Derek Teden, the second pilot was John De Keyser whilst the other WOp/AG was William Kent. They were tasked to carry out the SA5 patrol, this was a figure of eight pattern patrol over the North Sea intended to detect a sea-borne invasion. The plan was for the aircraft to arrive in the area at 2300 hrs, carry out 2 circuits and return to base, Jim's aircraft failed to return. Searches were carried out by 6 aircraft at first light and then by a further 6 aircraft later in the day, however nothing conclusive was found.

It is not known what caused the loss of the aircraft although Jim's OC, Wing Commander Constable Roberts, thought it most likely that they had encountered a German fighter patrol.

The scale of losses during the Second World War stagger the imagination; Coastal Command lost 11,000 men and 2000 aircraft over the course of the war, 206 Squadron in 1940 alone lost 56 men and 28 aircraft. Jim is commemorated on the Runnymede Memorial alongside 20,000 others who were lost on operations from the UK and Europe and who have no known grave."

In July 2010 I noticed a photograph of Hudson T9303 in the 206 Squadron Association Newsletter for June 2010. This is the same Hudson that Jim Steel's crew failed to return in on the 16th October 1940. The crew listed in the 206 Squadron Roll of Honour are as follows...

-

P/O D.E.Teden (90486)

-

P/O J.L.Derkeyser (79166)

-

Sgt Kent (518350)

-

Sgt Steel (644325)

Hudson T9303

Failed to Return - 15th October 1940

Eric Walker

Rank: Warrant Officer

Number: 1310806

Joined 206: ??/??/19??

Flew with Ken: 0 times

Born: ??/??/19??

Died: 02/12/1944

In 2009 I received a message on the website Guest Book from Trudy Hindmarsh. Trudy was investigating her Uncles brother, Warrant Officer Eric, who was a Wireless Operator / Air Gunner in 206 Squadron. She had seen the Roll Of Honour list on the website and spotted Eric's name on it with the following reference:

"W/O E.A.Walker - 1310806 - Death Presumed - 02/12/44"

Having checked through the Roll Of Honour list I spotted entries from the same date, all with 'Death Presumed' against their names. It's logical that these were all part of the same crew and its enough men to assume it was a Liberator crew:

-

S/L R.H.Harper - 41177

-

F/L K.G.Elliot - 82190

-

P/O W.Charters - 184685

-

P/O D.P.L.Hawkins - 413487

-

W/O F.R.Hall - 129181

-

F/S G.S.Marshall - 1337473

-

F/S R.Peats - 1685242

-

F/O S.Tulloch - ?

-

W/O E.A.Walker - 1310806

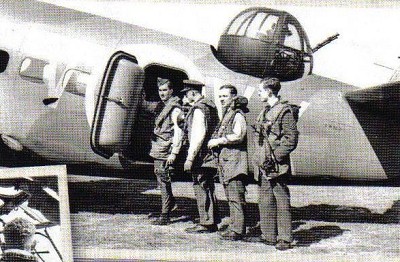

Trudy supplied the following photographs of Eric from his time in the RAF along with his wife and daughter.

W/O Eric Walker Eric and Elva Pat

Eric Walker within a group shot